A big reason for December’s big market crash (the S&P 500 plunged 17% in three weeks and the Nasdaq fell into a bear market) was fear that the Fed might blindly hike rates three times in 2019 despite rising recession risks. A 180-degree dovish pivot by the Fed helped drive the strongest Q1 rally in 32 years.

Then in May trade war escalation helped cause a nearly 7% market decline (the worst May for stocks in 10 years and the second worst since the 1960s). The Fed again saved the day when Chairman Powell told reporters at a conference that the FOMC would cut rates as many times as it took to prevent a trade war recession and buy a lot of long bonds as they did during the last crisis.

Given how often the Fed seems to change policy based on the stock market’s volatile swings, it’s easy to understand why the “Fed Put” is a common belief among investors.

However, even though many analysts also believe that the Fed could continue saving the day on Wall Street, history shows us that betting your nest egg on rate cuts averting a strong market decline could be a risky move.

Even Wall Street Pros Believe in the Fed

On June 10th Mark Schofield, head of Citigroup’s Global Macro strategy team wrote a note to the bank’s clients that

“Tensions are mounting and the outcome looks more likely to be driven by politics than economics.” Most concerningly he wrote that Citigroup now considers Trump taking “a hard line” on trade the base case, which means the bank now thinks the most likely outcome is full 25% tariffs on all Chinese imports sometime this year, and 25% EU auto parts tariffs as well.

The outcome for the market from Citi’s base case scenario is a 20% stock market plunge (from the all-time high), and 10-year yield crashing to 1.5% “maybe lower”. That’s a scary sounding scenario but Citi also says that should the Fed cut three times (0.75%) then it believes the market would set new highs this year.

Mind you what Chairman Powell said last week, that kicked off this very pleasant market rally, is merely that the Fed was watching the economic data for signs that anything (including the trade war) might be slowing the economy enough to risk a recession.

In other words, Citigroup, like many investors seems to think that the market would ignore much worse economic (and corporate earnings) fundamentals and just go up because rates might get much lower.

The logic behind the Fed put goes like this. Stocks historically have a roughly 3% EPS risk premium over risk-free 10-year Treasuries (so earnings yields are 10-year yield +3% on average). Thus if 10-year yields fall low enough, say 1%, then a forward PE on the market of 25 (it’s about 16 right now) becomes theoretically justified. If the Fed were to buy enough long bonds to drive yields to zero (as they are in the EU and Japan) then, theoretically, a forward PE of 33 on the S&P 500 could be justified.

In the face of such potential multiple expansion, fundamentals would take a back seat and barring a complete economic collapse, stocks might go up even if the earnings deteriorate.

This is the kind of “bad news is good news” thinking that largely explained much of rally over the past decade, when both earnings and economic growth was relatively weak. But while it’s undeniably true that the Fed’s dovish pronouncements hold the power to move the market higher in recent times. It’s not a good idea for investors to assume the Fed can, or will even try, to avert a strong market downturn.

The Fed Is Likely to Prevent Another Great Recession Style Meltdown But Can’t (And Won’t Try) to Avert All Future Corrections

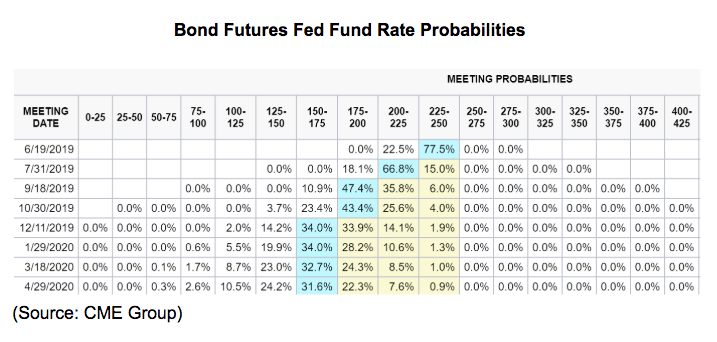

Right now the bond futures market is pricing in a 99.1% probability that the Fed will cut by April 2020, and a zero percent that it will raise rates.

Specifically, the bond market now expects the first of three rate cuts to come in July, then again in September and the third in December. I certainly agree with the bond market that one or two cuts are likely necessary, given what the economic fundamentals are now telling us about the GDP growth rate for the rest of the year.

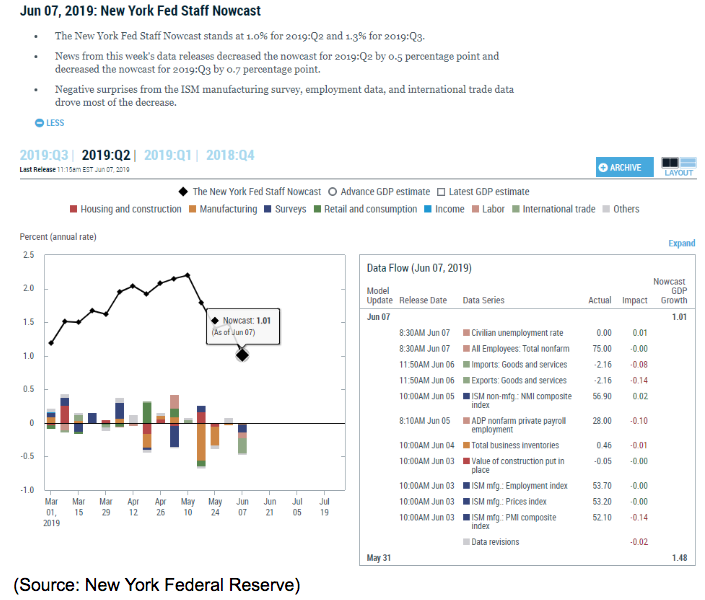

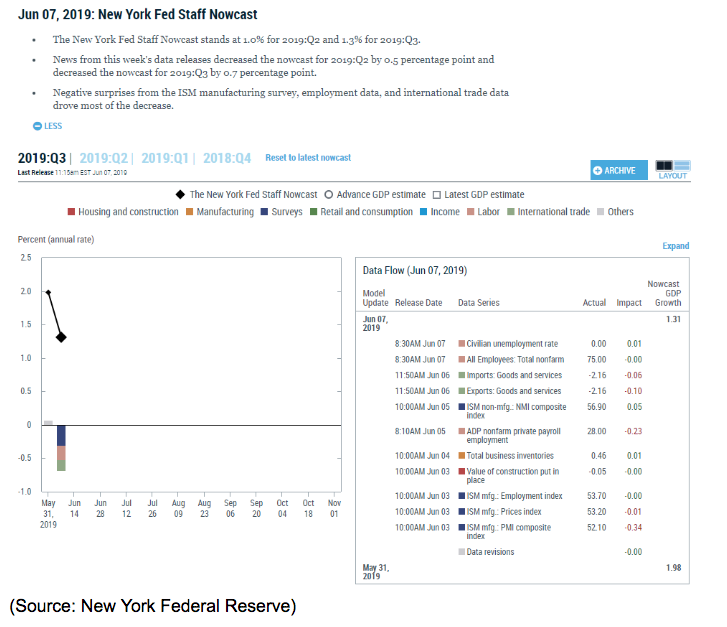

The New York Fed’s real-time GDP growth model, which factors in leading economic indicator reports as they come in, has fallen off a cliff in recent weeks. On May 10th, (the day China tariffs went up) the NY Fed estimated Q2 GDP growth was tracking for 2.2%. By June 7th it had plummetted to 1.0% mostly due to very weak trade data and a big downturn in manufacturing.

Q3’s growth, which the NY Fed is now able to estimate, is similarly weakening and now estimated to be tracking for 1.3%. That’s roughly 50% lower than the full year GDP growth consensus at the start of the year. And the final $300 billion China tariffs haven’t yet gone into effect.

Moody’s Analytics estimates that full China tariffs could reduce US growth by 1.8% annually, within 12 months of implementation. This effectively means that, while a 2019 recession is highly unlikely, a 2020 economic contraction could very well be in the cards, should trade talks fail to avert that largest and most economically damaging tariff round.

But that’s where the Fed put is supposed to save the day right? Indeed the Fed has confirmed that it will cut to zero (a total of eight times) if the economic data indicates it’s necessary. According to Moody’s eight rate cuts, within 12 months, should increase GDP growth by about 1%. That effectively means that should trade talks fall apart, the US might face -0.5% economic growth in 2020 without the Fed’s intervention, but cutting rates to zero could drive that up to +0.5%. That would still be horrible growth, but it would likely avert recession (if the Fed acts quickly enough).

So does that justify the belief in the “Fed put” and the notion that stocks can rise even in the face of worsening economic and earnings news? Not necessarily and here’s why.

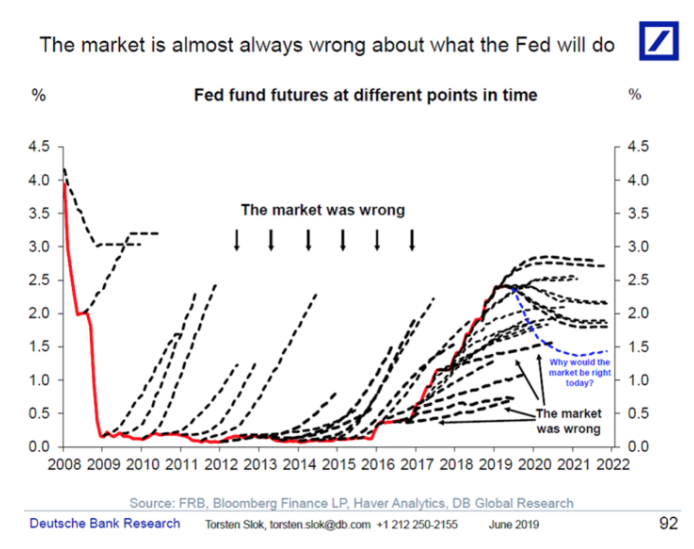

First, it’s important to remember that the bond futures market, while indicating what institutions think the Fed will do, isn’t God and is often wrong.

In fact, as Deutsche Bank recently pointed out, in the last 10 years the bond market has mostly been wrong about what the Fed was going to do. At best the bond futures market can tell us the general direction that the Fed is most likely to take next, but the timing and magnitude of its rate cuts/increases are far less certain.

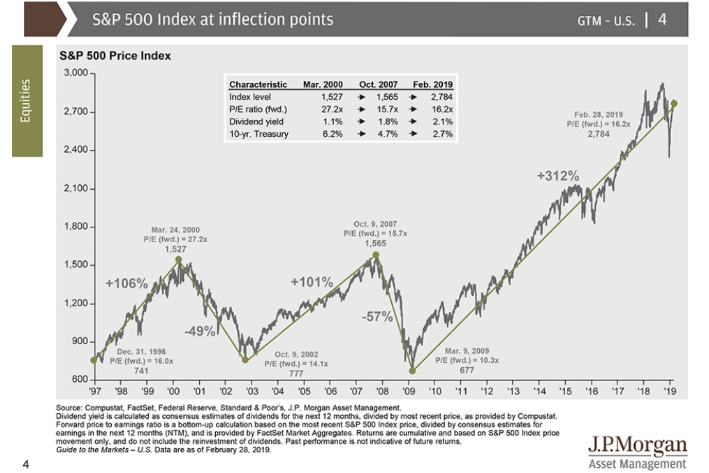

But there’s also a fundamental reason to not by into the “rates down stocks up” theme that the media likes to hype. Here’s a chart of the S&P 500 over the past 22 years, including key inflection point forward PEs.

Over the past 25 years (the modern era) the average forward PE for the S&P 500 has been 16.2, indicating this is a good estimate of “fair value” for stocks. On March 24, 2000, when the market peaked during the tech bubble (and achieved the highest valuations in history) the forward PE ratio hit 27.2. Today no one questions that this was an absurd valuation. So now ask yourself what if 10-year yields were to go to zero as they are in the EU and Japan. Would a 33 forward PE suddenly make sense to you?

I certainly wouldn’t be willing to invest in a broad market index fund at such insane bubble valuations, especially if corporate profit growth had slowed to a crawl (as would be the case in any scenario where 10-year yields go to zero).

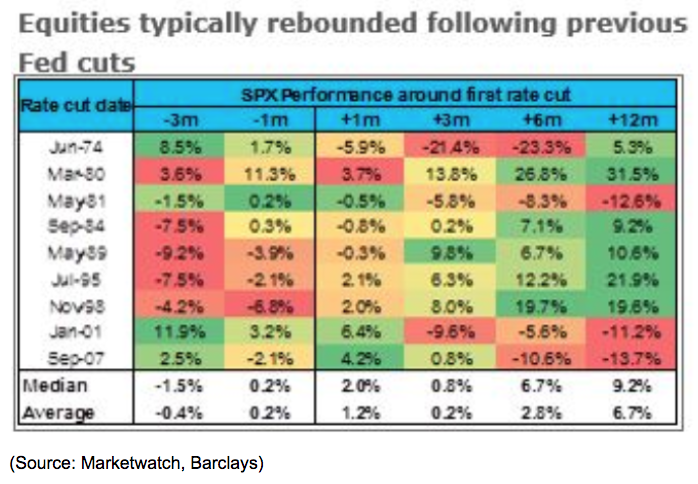

But perhaps the most convincing evidence of the limitations of the Fed’s power to drive stocks higher in the face of weakening fundamentals is what happened the last nine times the Fed began cutting rates due to a weak economy.

At first glance, this table from Barclay’s might indicate that the Fed Put is real. It’s certainly true that the market was rather weak just prior to the Fed beginning its last nine rate-cutting cycles, with an average 3 month gain of -0.3%. It’s also true that the average 12-month returns following the first rate cut (and most of the time more followed) was 6.7% with a median gain of 9.2%.

Aha! That proves it! The Fed put is real and can be relied upon right! Actually no. Since 1926 the market has posted positive returns in 74% of years. And the market’s historical return is 9.1% CAGR, thus the reason that most analysts predict a roughly 10% return at the start of every year (a high probability prediction).

The 6.7% average 12-month return following rate cuts is actually historically weak, and even the more impressive 9.2% median gain is merely the average market return.

Now there is good news for “Fed Put” believers. That would be that the Fed’s promise of more QE (bond buying) in the future (most likely 10-year Treasuries meaning ETF IEF is a potentially good recession hedge for your portfolio). In addition, some members of the Fed have previously discussed the possibility of directly buying US stocks (as the Bank of Japan has done with ETFs in that country for decades).

However, it’s important to note that the Fed isn’t likely to undertake either QE or direct equity purchases unless we’re in a recession, and it likely won’t buy stocks unless the market is melting down (ala 2008 and 2009). In effect, that means that the doomsday predictions of some permabears, of a 60% to 70% market crash, are extremely unlikely. Such a collapse in equity prices would likely require an epic crash in economic fundamentals for which plausible catalysts currently don’t exist.

And if stocks were to dive 40% (one popular definition of a crash among analysts) the Fed would likely step in with a lot of bond buying that would likely put a floor under the market long before we reached levels the doomsday prophets predict.

This is why my personal capital allocation plan for a recession or bear market calls for watching the macro fundamentals (leading indicators including the yield curve) and adapting what percentage of my monthly savings goes into new stocks vs cash (actually bond ETFs).

While in normal economic times (low 12-month recession risk) I invest 100% of monthly savings into the most undervalued blue-chip dividend stocks on my watchlist, as recession risk rises (currently about 40%) I cut that down in 20% increments. Right now I’m investing 80% of my monthly savings into stocks and won’t go to zero (all new money into bonds) until November 23rd, should the macro data continue to worsen.

Whenever stocks hit -20% (official bear market) I will immediately begin selling my bonds to buy stocks. That’s because I personally always target the most undervalued companies, which even today are trading at March 2009 style valuations (my most recent portfolio buy was for a chipmaker at 10.7 times forward PE, vs S&P 500’s 10.3 on March 9th, 2009 PE).

Should stocks fall another 17% or so, I’ll be able to pick up blue-chip bargains at PEs of 5 to 9, and price/cash flows of 3 to 8. Those are literally private equity valuations, a higher risk/illiquid investing strategy where funds strive for 20% CAGR five-year total returns. I’m aiming for roughly 15% to 20% returns as well, but with a low-risk dividend growth strategy that merely attempts to buy the most hated quality companies today, due to fears over a bad next year or two, because I believe that each company’s cash flow and dividends will be nicely higher in 5+ years.

And since the Fed has pretty much told us that QE 5 is coming in during the next recession, I’m not going to idly stand by and watch quality companies trading at 3 to 8 times cash flow pass me by waiting for even better bargains during a deeply unlikely 60% to 70% crash that the Fed would likely do anything to avoid (including printing infinite amounts of money to directly buy US stocks).

Bottom Line: The Fed’s Rate Cutting Will Likely Avert a Recession, But It Might Not Necessarily Prevent the Next Bear Market

Don’t get me wrong, I’m not one of those Fed haters who think Powell and company are conspiring against the President or trying to “take away the punchbowl”. While I do consider last year’s four rate hikes to have been an avoidable mistake I have confidence that the Fed remains a non-partisan group of technocratic data-driven wonks who have their eyes firmly fixed on the macroeconomic fundamentals.

Which is why I consider a recession to be the smaller (40%) probability event, because up to eight rate cuts could boost GDP growth by about 1%, according to Moody’s economic models.

Given the current 2019 growth rate, plus the dry powder Powell has at his disposal, it’s unlikely that a US/China trade war, even if it lasts through all of 2020, will actually cause negative economic growth.

However, as far as what investors should expect over the coming year, it’s important to keep in mind that historically rate cuts have a very limited ability to actually prevent corrections or bear markets.

Yes, in today’s era of historically low rates and inflation, the Fed has a lot of market-moving power. That’s one reason that market timing is a bad idea, and sticking to your long-term investment strategy in the face of high headline risk and market volatility remains the most prudent move.

Eventually, we’re likely to get a recession (though a historically normal one that’s far milder than 2007-2009). At which time anyone who believes that low rates are all that’s needed to maintain a strong market rally is almost certain to be painfully disappointed.

Ultimately stock prices are a function of corporate earnings, cash flow and dividends (the fundamentals). Which is why I continue to focus on those, both for the broader market and my individual holdings.

Never forget that the time to think about risk management is when the sun is shining and the market is marching higher (as it does in 74% of all years), not during sharp declines like we saw in May.

The Fed is likely to save the longest economic expansion in history (barring a truly historical screwup by our political leaders), but it doesn’t have the power to avert a future bear market, nor is it likely to try.

About the Author: Adam Galas

Adam has spent years as a writer for The Motley Fool, Simply Safe Dividends, Seeking Alpha, and Dividend Sensei. His goal is to help people learn how to harness the power of dividend growth investing. Learn more about Adam’s background, along with links to his most recent articles. More...

9 "Must Own" Growth Stocks For 2019

Get Free Updates

Join thousands of investors who get the latest news, insights and top rated picks from StockNews.com!