Few people, even value investors, truly like it when stocks crash, as they did in late 2018 (the S&P 500 suffered the worst correction since 2009 and the Nasdaq plunged into a bear market).

That’s why so many people try to guess what might cause the next great market crash, ala the 50+% declines suffered during the tech bubble bursting and the Financial Crisis. While it’s not possible to predict with certainty when or what might cause the next bear market, it’s useful to be aware of the risk factors facing the economy and the stock market at any given time.

While the escalating trade war is certainly a major risk to watch closely over the next few months, there happens to be a much larger threat looming over the short-term horizon. One that is getting far less attention from the media, but is far more likely to cause the kind of market meltdown that so many people have feared over the years.

Here’s what you need to know about this mostly ignored threat, and what you can do to best prepare your portfolio should the worst case scenario occur.

The Debt Ceiling is a Far Bigger Threat to Stocks

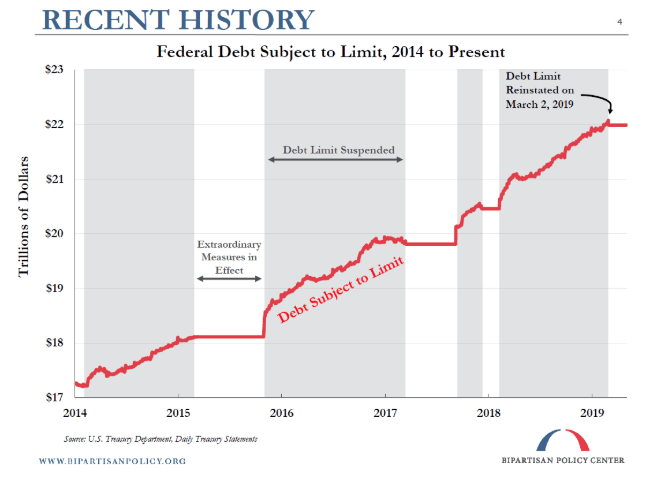

The debt ceiling (originally set at $39 million back in 1939) was created to streamline federal borrowing. This limits the amount the US Treasury can borrow at any given time. On March 2nd it was reinstated after being suspended on February 9th, 2018 by the 2018 Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018, at $22 trillion. According to usdebtclock.org, which estimates the national debt in real time (as well as dozens of other important metrics) on May 14th the US national debt was $22.29 trillion.

When we approach or exceed the debt ceiling Congress raises it (they’ve done this dozen of times under presidents from both parties) and the President signs it into law. The Treasury is able to move money around (so-called “extraordinary measures”) to keep the US paying its bills for several months should our increasingly dysfunctional government act in time.

Since March 2, these extraordinary measures have been in effect.

The only two times the US has ever defaulted on its debt were in the War of 1812 (literally due to an inability to send out checks due to the conflict) and a “mini-default” in 1979 in which 4,000 checks worth $122 million were delayed in being sent due to technical issues at the Treasury Department.

The idea that the US government always pays its bills (including interest and principal on Treasury bonds and bills) is literally at the heart of the global economy. Portfolio asset allocation, for retail investors, pension funds, insurance companies, banks, and endowments/charities are all predicated on the idea that US debt is “risk-free”. The confidence the world’s bondholders have in US debt is also the key reason the US dollar is the preferred reserve currency of the world and what’s kept US borrowing costs so low for decades, despite steadily rising national debt.

Financial institutions, like banks, use US Treasuries as collateral, so-called “tier 1 capital”. The stable values of these bonds is what banking leverage is based on, both under Dodd-Frank and the global Basel III accords.

And according to Forbes, The Federal government, Social Security, Medicare, Military and the Federal Retirement system own 27% of the debt, meaning that a default could quickly make some of America’s most important programs and institutions insolvent (social security checks might not go out, impacting the personal finances of millions of retirees).

Should the value of US treasuries suddenly fall due to bond market fear, then it could trigger a financial crisis of unknown severity, as credit markets would suddenly have the very core assumption of short-term liquidity invalidated.

A debt ceiling showdown in which the US came very close to defaulting in 2011 cause S&P to downgrade US debt from AAA to AA+, a rating hit that we have never recovered from (and that will cause slightly higher borrowing costs for decades). Moody’s and Fitch, though upset over the event, didn’t change their ratings, though that debt ceiling scare did cause a 19.6% stock market correction.

In March 2011 then-Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke (who was part of the “council to save the world” during the Financial Crisis) warned that a debt default would cause financial “chaos” and likely undue the economic recovery, then still in its infancy.

Current Fed Chairman Jerome Powell similarly thinks debt ceiling uncertainty is a grave economic risk recently saying “It’s beyond even considering that the United States would not honor all its obligations and pay them when due. It’s just something that can’t even be considered.”

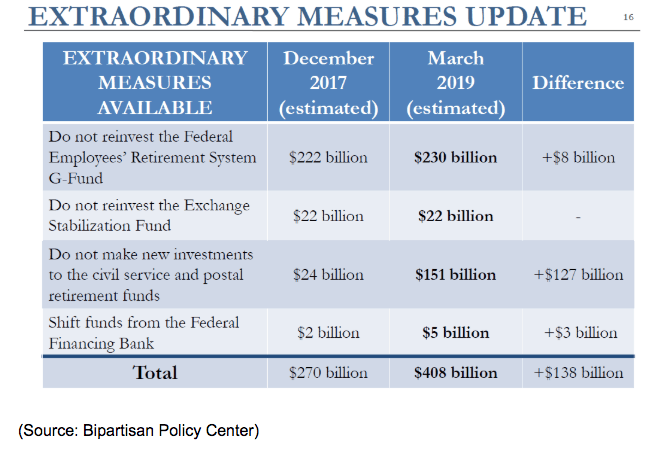

The Bipartisan Policy Center estimates, using the latest available budgetary data (publicly disclosed), how much of a cushion Treasury has to work with via extraordinary measures. At the end of March, it estimated Treasury could move $408 billion around to keep the US out of default.

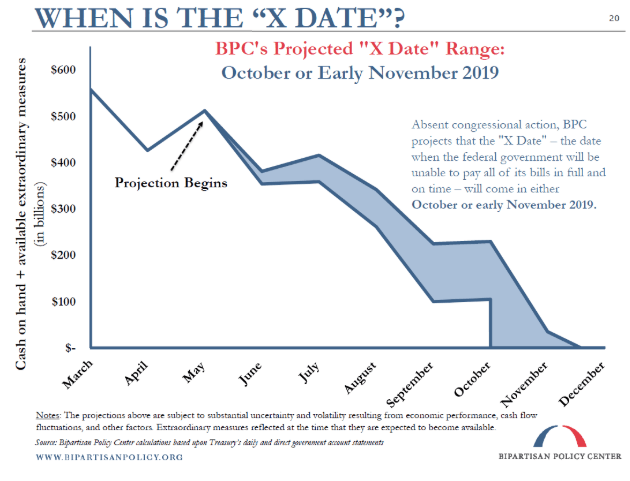

On May 9, the BPC updated its estimate to $600 billion, after tax receipts for fiscal 2018 came in slightly above expectations. However, that merely moves the “X date”, when Treasury is completely out of options and must pay out all liabilities purely with incoming cash (like payroll taxes) to October/early November.

So that’s why the debt ceiling is important, and the latest estimates of how long Congress (and the President, who must sign any debt ceiling increase) have to act.

In recent years Congressional Republicans have insisted that any increase in the ceiling would be matched (sometimes 2:1) by cuts to future spending (generally entitlement programs). The risk this time is that a GOP controlled Senate, which must vote to pass any bill originated in the Democrat-controlled House (constitutionally all budget bills must start in the House) might refuse to pass a clean increase (Democrats have indicated zero interest in budget cuts).

And even if the Senate were to pass a clean ceiling raise, President Trump, ever the wild card (and who has joked about defaulting on the debt in the past) might decide to win policial points (likely a horrible miscalculation if he does this) by appearing fiscally conservative.

In other words, partisan gridlock between a divided Congress and the Whitehouse could potentially result in a high stakes game of chicken that might end in disaster.

One that according to former Treasury Secretary Tim Geithner, would quickly cause interest rates (of all kinds) to rise, the dollar to drop, and the Federal Government to be unable to pay its employees (shut down on steroids). If the trade war puts us at risk of a correction, a debt default, depending on how long it lasts, could put us into a complete (though likely short-lived) market meltdown.

How You Can Protect Yourself

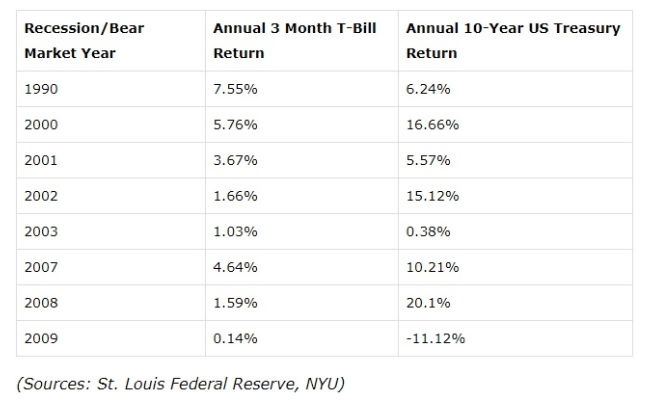

Normally proper asset allocation, meaning owning the proper mix of stocks/bonds/cash (like T-bills) is the best way to protect your portfolio and net worth from temporary market freakouts. In the case of a US debt default that might not work.

After all, if the bond market loses confidence in the “risk-free” nature of US treasuries and t-bills, then these assets might decline in value, rather than rise, due to a “flight to safety” in which T-bills and bonds appreciate in value as investors sell stocks and seek to preserve that capital into something that’s guaranteed not to lose money (if held until maturity).

In the case of a true US debt default, bonds might potentially fall off a cliff, which would mean investors need to watch bond yields for signs that the bond market is signaling the risks of a debt default are higher than before.

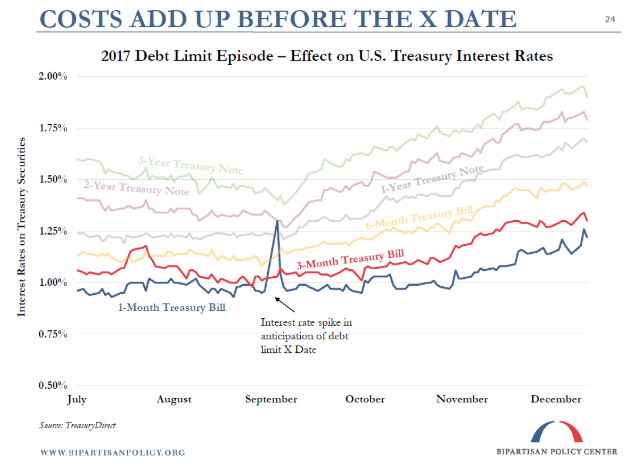

While historical data can only provide a rough guide to what will happen later this year, the last debt ceiling deadline saw a roughly 30% spike in the 1-month Treasury bill yield.

Given that the Senate and Whitehouse were in the same hands as this time, any significantly higher increase in short-term yields might indicate that “the smart money” is betting that a default might be imminent.

If that were to happen it might be a good idea to take your bond/cash allocation and convert it into actual cash (sitting in your brokerage account). That way you will still have the same safety cushion that can meet your financial needs during a correction/bear market (and keep you from having to sell stocks at firesale prices) and limit your downside risk should US treasuries significantly fall in value.

Note that I’m not necessarily saying that bonds will certainly lose their safe haven status. During the 2011 debt ceiling crisis (when the US lost its S&P AAA status) bonds actually rose in value as money poured out of stocks and into bonds.

However, the idea behind preparing for long-tail risks (US home prices declining 30% nationwide was once thought impossible until it happened and caused the Global Financial Crisis) is that you need to have a reasonable plan in case the worst case scenario actually occurs.

For example, the Black Monday, October 1987 stock market crash (22% one day decline without warning or particular cause) was, under standard statistical models, though to be a 1 in 4 billion year event (so basically impossible). Instead, Harvard statisticians concluded such a market crash can be expected to occur, on average, once every 104 years. Or to put another way, on Wall Street, the “impossible” occurs with alarming and is thus worth planning for.

I will be using this approach, of watching the 1-month treasury yield in September and October, to act as a warning signal to me about whether or not I should sell my own bond ETFs (where I keep my cash) and recommend friends and family consider doing the same.

Bottom Line: Long Tail Risks Are Important to Keep In Mind, But Don’t Lose Sleep Over Them

Don’t get me wrong, I’m not trying to scare anyone into selling all their stocks and piling into cash (actual cash, not t-bills) or gold. My goal here is to merely point out the long-tail risk that a debt ceiling showdown and possible US debt default might represent.

While it’s a low probability event (just like the housing meltdown or Black Monday crash of 1987 was), long-tail risks are the kind of financial doomsday scenarios that happen from time to time and sometimes with world-changing consequences.

The debt ceiling represents a unique risk in that it threatens the very core of the modern global financial system, the notion that US treasuries are “risk-free” assets. That fact, which has held true nearly without exception since our nation’s founding, is baked into the business models and investing strategy of billions of people, ranging from pensions to insurance companies to global retail investors.

It’s also the reason the US dollar is the world’s preferred reserve currency, and a major reason the US has enjoyed historically low borrowing costs for so long. There is no sugar coating it, a US debt default would be a truly game-changing event, that could have far larger and potentially permanent consequences for the entire global financial system.

The good news is, that while such an event could potentially trigger a much larger financial crisis than we saw in 2008-2009, the consequences of this “financial nuclear war” are so horrifying that the US isn’t likely to risk going down that road.

But I still consider it worthwhile to keep this final, and by far the largest, stock market threat of 2019 in mind, when deciding how to allocate new money in your portfolio. Should no progress be made on the debt ceiling by September, and or should President Trump start to threaten a default, then the standard asset allocation strategy of holding treasury bonds or t-bills might not work this time.

While I won’t be advising family or friends to liquidate their entire portfolios ahead of a possible worst-case scenario in October or November, should the risks of calamity mount (major spike in 1-month T-bill yields), I would recommend you consider holding actual cash (not equivalents) sufficient to meet your near-term expenses.

That is the best way to avoid becoming a forced seller (to pay the bills) during what might be a short, but especially brutal market panic and plunge.

About the Author: Adam Galas

Adam has spent years as a writer for The Motley Fool, Simply Safe Dividends, Seeking Alpha, and Dividend Sensei. His goal is to help people learn how to harness the power of dividend growth investing. Learn more about Adam’s background, along with links to his most recent articles. More...

9 "Must Own" Growth Stocks For 2019

Get Free Updates

Join thousands of investors who get the latest news, insights and top rated picks from StockNews.com!