There is no question that one of the reasons for late 2018’s market crash (the worst correction in 10 years) was driven by fears over the Fed blindly hiking us into a recession.

The Fed doing a 180 and frequently telling the credit markets that it would “be patient” about future rate hikes, and then later canceling them entirely, is a major reason the S&P 500, Dow, and Nasdaq enjoyed their strongest Q1 rally in 32 years.

Then when the trade war ramped up in last month, and sent stocks plummetting into their worst May in 10 years (and the second worst since the 1960s), it was the Fed once more stepping in with soothing words about possible rate cuts and future bond buying, that helped drive a 7% June rally that now brings us within about 1% of the market’s all-time high.

While it’s certainly true that now isn’t the time for excessive caution, since there isn’t much reason to worry about a recession yet, it’s also important to avoid drinking the rate cut Kool-Aid and getting too euphoric. That’s because the simple truth is that long-term investors don’t have much to fear from rising rates, nor will benefit much if rates soon go to zero

Rather focus on protecting your nest egg, and making the right portfolio choices during this strong rally, to maximize the chances of achieving your long-term financial goals.

Don’t Drink The Rate Cut Kool-Aid…

It’s not hard to understand why investors might THINK that low rates are great for stocks. After all, the longest bull market in history has occurred over the past decade, a time of the lowest rates in history and rather anemic economic growth and corporate earnings growth that is basically in line with historical averages (but driven in part by debt-funded buybacks).

There are actually two plausible sounding reasons that low rates might result in rising stocks, even during times of weak fundamentals (the “bad news is good news” theme that’s so popular right now).

The first is that, theoretically, lower interest rates justify high stock valuations (such as PE ratios) because fundamentally companies are worth their future cash flow, discounted to the present. The discount rate that determines fair value for stocks or the broader market, has traditionally been viewed as the risk-free rate (ie 10-year US treasury yield) plus some risk premium. So hypothetically, assuming all other things are held equal, lower long-term rates are good for stocks because it makes future cash flow worth more in the present.

The second reason is tied to the first, and perhaps easier to understand. Stocks are just one asset class and historically compete with bonds for attention and investor dollars. If bond yields are low, as they are today, then bonds look less attractive and “the hunt for yield” might force more money into stocks, driving up prices and valuations.

However, while these two ideas can be somewhat true in extreme situations (like rates near zero), they are highly simplistic and not backed up by history.

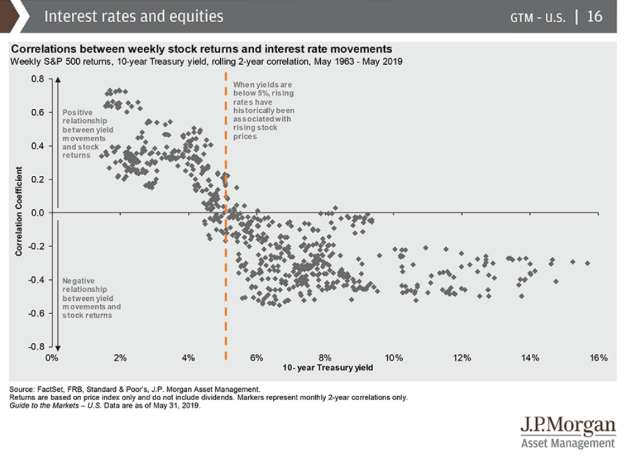

Between 1963 and 2019 stocks actually did better when rates were rising, as long as the 10-year yield wasn’t 5% or higher. That’s because long-term rates are set by the bond market, based on long-term inflation expectations. In other words, a strong economy, which causes higher inflation and thus higher interest rates, is good for stocks, because it means stronger cash flow growth.

That’s the thing that the “bad news is good news” crowd seems to forget. Super low rates don’t happen in a vacuum (which the “all else being equal” nature of valuation models assumes) but during times of economic/financial stress.

Or to put it more simply, stock valuations are not purely based on interest rates, because if they were then stocks would do best during recessions, when interest rates are at their lowest.

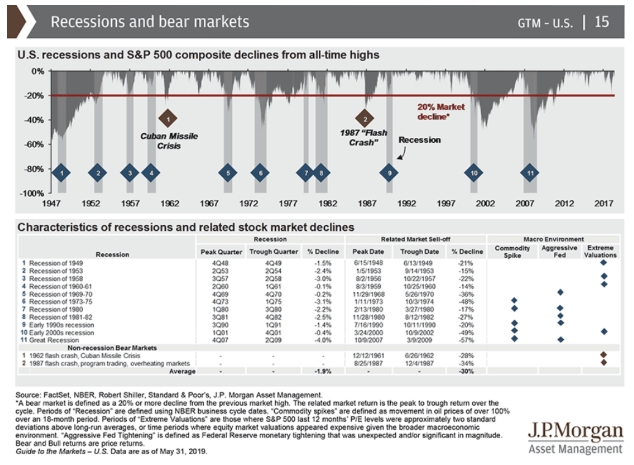

Yet since 1946, every recession has resulted in a significant market decline, with the average bear market seeing stocks decline by 30% over about 12 months. So does that mean that I’m saying this rate cut rally is false and you should sell all your equities ahead of an inevitable market crash? Certainly not.

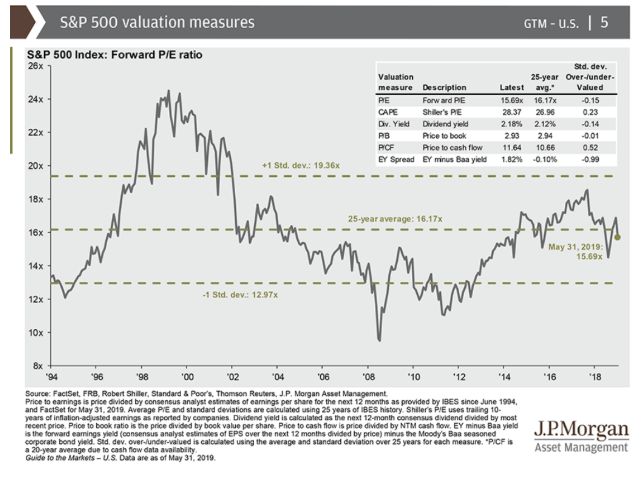

Despite what some doomsday prophets might have you believe, the market is not, in fact, in a crazy bubble and set to crash 70% (I’m looking at you John Hussman). Including today’s 1.5% rally (as I write this), the forward PE on the S&P 500 is about 16.7, which is just slightly higher than its 25-year average. And while true that the CAPE is elevated, as are the market’s price to cash flow and price to book ratio, neither one is at levels that indicate the market is set for a major downturn.

And other valuation metrics, like dividend yields and earnings yield spreads, are near historical fair value or even point to stocks being slightly undervalued. So what does this mean investors should do? How should you manage your portfolio in an environment of rising recession risk, a lot of trade war uncertainty, but also rate cut euphoria?

…Instead, Make Sure You’re Money Is Safe In A Well Built Portfolio

I can’t give specific advice to any single investor, because what’s right for you will depend on numerous specific factors like your goals, time horizon, risk tolerance, savings rate, etc. But it’s worth remembering the words of Benjamin Graham, Buffett’s mentor, the father of value investing, and the 3rd best investor in history (20% CAGR total returns from 1934 to 1956 vs S&P 500’s 12%).

“The best way to measure your investing success is not by whether you’re beating the market, but by whether you’ve put in place a financial plan and a behavioral discipline that are likely to get you where you want to go.”

In other words, don’t obsess over what the market itself is doing, but build a portfolio based on an appropriate long-term plan that’s most likely to meet your personal needs, and factors in how much risk (volatility tolerance) you actually have.

When it comes to individual stocks or sectors (for those that like to passively invest in ETFs) you can always rely on the fact that, no matter what the broader market is doing, something great is always on sale. For example, even with the S&P 500 now within 1% of its all-time high, there are dozens of quality dividend growth blue-chips trading at 20+% discounts to fair value.

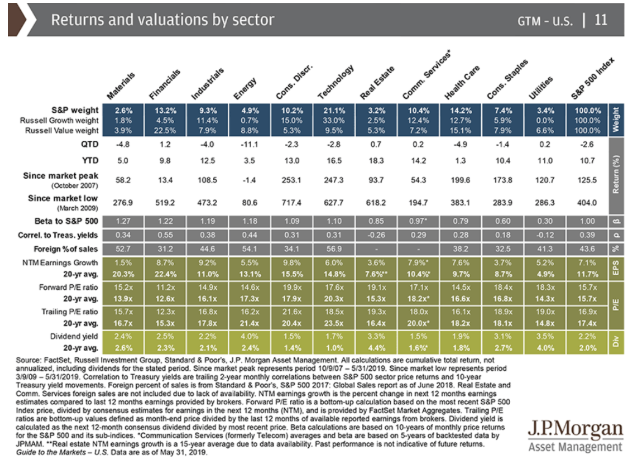

Or as you can see in this table, at the end of May six out of 11 sectors were trading (based on forward PE) at levels below their 20-year averages, which is a good proxy for fair value.

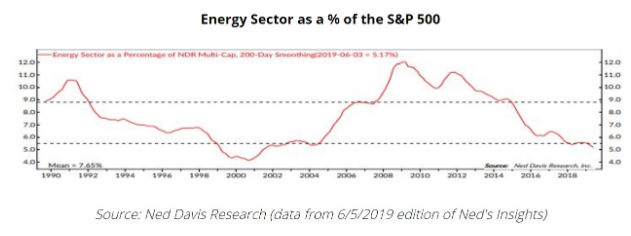

Granted those valuations are now up a bit, but there are still beaten down sectors like energy to consider. In fact, as a percentage of the S&P 500’s market cap, energy is now tied for its most undervalued level since 2004 and only during the crazed tech bubble years were energy stocks better buys than today.

But let’s also remember that more important than what stocks you’re buying is your overall asset allocation, meaning what mix of stocks/cash/bonds you own.

Despite what many investors think stocks are NOT a bond alternative, but a separate asset class, owned to deliver income but also to smooth out portfolio returns and give you stable/appreciating assets to sell during stock market declines.

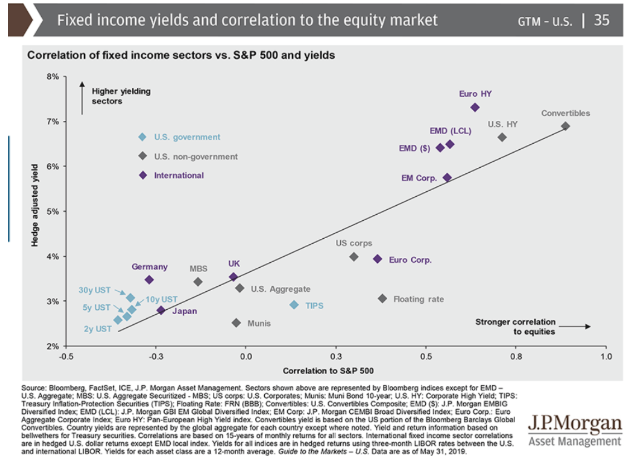

For example, sovereign bonds, like “risk-free” US treasuries are highly negatively correlated to stocks, at least most of the time. This is why long-term US treasury bond values tend to rise during market panics, such as during recessionary bear markets.

Times like these, when the market becomes silly and starts ignoring risks because “low-interest rates!” are a great time to take a look at your overall portfolio and make sure that rising stock prices haven’t caused your allocation into volatile stocks to get too high.

Use December’s 17% three-week crash or May’s 6.5% decline (a historically average pullback that occurs on average every 6 months since WWII) as a way to determine whether or not your portfolio holdings are actually appropriate for your risk tolerance. If you lost sleep in December or May, then you own too many stocks relative to bonds and should rebalance by selling some stocks to buy more bonds. In general, you want to rebalance your portfolio on a periodic basis, say every six months or annually.

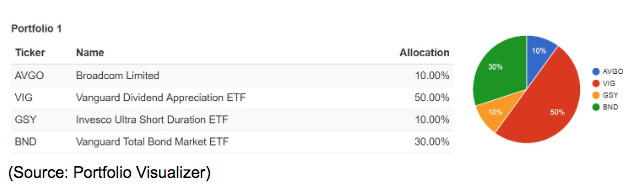

Here’s a perfect example of what I mean by an appropriately designed portfolio, based on the needs of the typical near-retiree, who plans to use some form of the 4% rule to pay bills during their golden years. This person is looking for the total return boosting power of a quality undervalued blue-chip, in this case, Broadcom, but also wants to minimize the risks of a single company failure blowing up their portfolio.

This is why this 60% stock, 40% bond portfolio (cash is in the form of ultra-short duration investment grade bonds) is 10% in Broadcom but 50% in VIG, a good proxy for a diversified dividend growth portfolio. Bond exposure is from BND, which is a low-cost ETF that owns a good mix of investment grade corporate and government bonds.

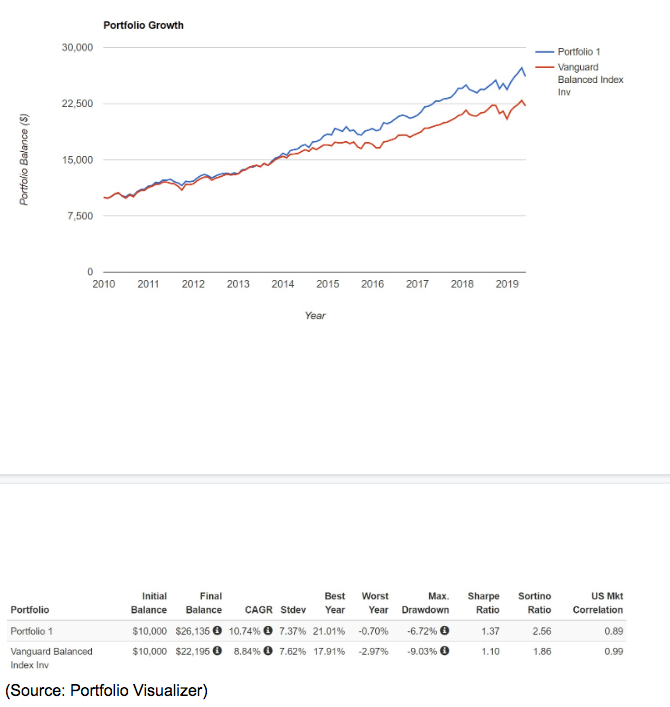

Over the past nine years, this portfolio would have beaten its benchmark (a standard 60/40 stock/bond portfolio) by 2% annually, while achieving smaller peak declines and its worst annual return was just -0.7%. This is why the reward/risk ratio (Sortino ratio, total returns minus risk-free return/negative volatility) was 38% better than a regular 60/40 portfolio.

Note as well that the 10.7% CAGR returns of this model portfolio, while not keeping up with a 100% S&P 500 portfolio (about 15% CAGR total returns) still managed to beat the market’s historical 9.1% CAGR. Granted this was during the longest bull market in history, and future returns will be lower (AVGO is likely to deliver about 17% total returns vs 34% over the past nine years), so you can’t count on future returns being as good.

But the point is that the right mix of stocks, bonds, and cash (via low-cost ETFs) is the right way to protect and grow your nest egg, no matter what the volatile stock market does over the next month, quarter or decade.

Bottom Line: Investors Appear to Be At Risk of Getting Drunk on Rate Cut Euphoria So Caution is Warranted

Don’t get me wrong, I’m not saying that stocks are now set to crash. If I believed the macroeconomic factors were pointing to such an event, I wouldn’t still be steadily buying dividend blue-chips for my retirement portfolio, where I keep 100% of my life savings.

But this article is about cautioning investors to avoid buying into a “bad news is good news rally” on the premise that low-interest rates are all that are needed for the market to go up.

If low rates were truly the only bullish catalysts necessary for investors to prosper, then the best market returns would occur during economic recessions when interest rates fall to their lowest levels.

This is why I advise using this current rate cut rally to take a look at your entire portfolio and determining whether or not your asset allocation remains appropriate. Strong rallies, including the longest bull market in history, might mean you’re too heavily weighted in stocks. If so then corrections like December, or May’s historically average pullback, can expose you to greater emotional strain, potentially enough to result in costly mistakes like panic selling at the worst possible time.

Decades of market studies, as well as the wise words of the greatest investors in history, teach us that long-term investing success isn’t about bagging huge winners, but rather avoiding big mistakes. Never forget what Charlie Munger, a legendary value investor and Buffett’s right hand at Berkshire for decades, famously said about the “secret” to his and Buffett’s success

“It is remarkable how much long-term advantage people like us have gotten by trying to be consistently not stupid, instead of trying to be very intelligent.”

About the Author: Adam Galas

Adam has spent years as a writer for The Motley Fool, Simply Safe Dividends, Seeking Alpha, and Dividend Sensei. His goal is to help people learn how to harness the power of dividend growth investing. Learn more about Adam’s background, along with links to his most recent articles. More...

9 "Must Own" Growth Stocks For 2019

Get Free Updates

Join thousands of investors who get the latest news, insights and top rated picks from StockNews.com!