I think we can all agree that it would be great to be as rich as Warren Buffett (the second richest man in the world after Bezos loses 50% of his shares in his divorce). Of course, few people can realistically expect to recreate the man’s epic 20+% CAGR total returns over the past 53 years, which he himself has admitted.

But standing on the shoulders of giants by adopting the time tested lessons of the greatest investors in history (like Buffett) is a great way to both improve our own investing returns, as well as avoid costly mistakes that can dash our financial dreams.

So let’s take a look at what lessons we can learn from Buffett’s recently-admitted $3 billion mistake, and how that can hopefully set us up to grow our own wealth over time.

Valuation Is an Important Part of Risk Management Because…

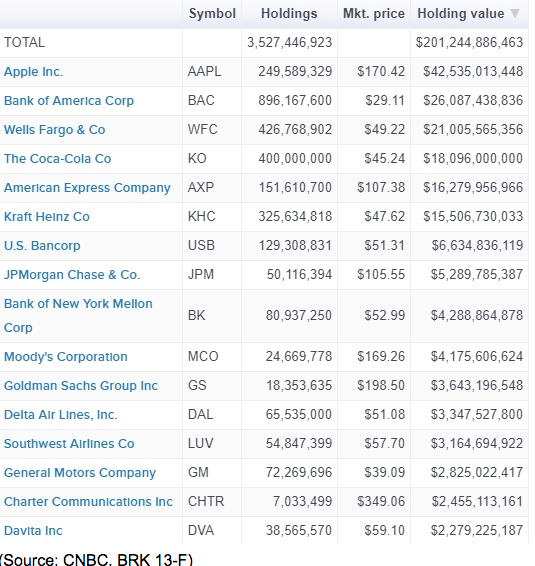

Berkshire Hathaway (BRK.B), Buffett’s company, just released its latest earnings, which included a $3 billion write-down on its 26.7% stake in Kraft Heinz (KHC).

That’s a pretty big mistake which came as a result of Berkshire’s team up with Brazilian private equity firm 3G Capital to buy Heinz in 2013 (which was a partially leveraged buyout). Berkshire then helped to finance the $49 billion merger with Kraft that created the world’s 5th largest consumer packaged food business.

Buffet recently told CNBC,“I was wrong in a couple of ways about Kraft Heinz…We overpaid for Kraft…It’s still a wonderful business in that it uses about $7 billion of tangible assets and earns $6 billion pretax on that…But we, and certain predecessors, we paid $100 billion in tangible assets. So for us, it has to earn $107 billion, not just the $7 billion that the business employs.”

Buffett is famous for his love of value investing, refusal to knowingly overpay for a company with famous quotes such as “it’s far better to buy a wonderful company at a fair price than a fair company at a wonderful price.”

In this case, he’s admitting that Berkshire ended up overpaying, not necessarily for Heinz itself (which was a cash-rich, wide moat and thriving company back in 2013), but during the merger with Kraft, which added extra M&A risk to an already large and complex deal.

According to the Harvard Business Review, 70% to 90% of big M&A deals fail, and it’s usually due to the use of too much debt to finance overpriced takeovers. In this case, even the legendary Oracle of Omaha, who prides himself a master of valuing firms, came up short.

What can you personally take from Buffett’s $3 billion mistake (which might prove larger in the end)?

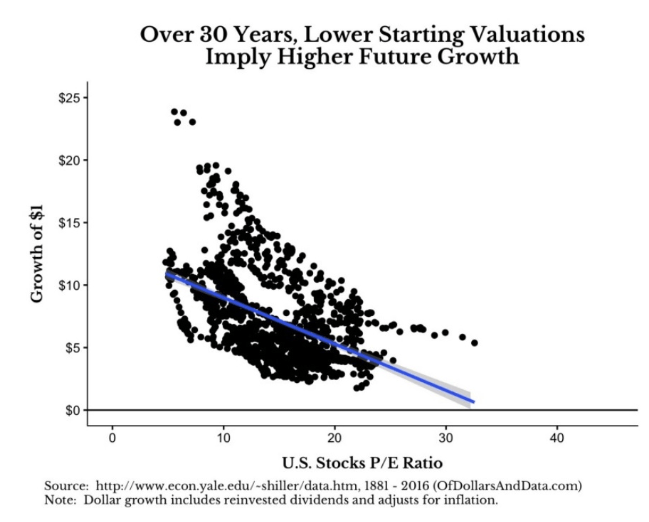

Valuation ALWAYS matters, and you should never knowingly overpay for a company, no matter how good you think it’s fundamentals or growth prospects are. A Yale study found that starting PE is closely correlated to total returns out to 30 years. In other words, buying a company at a ridiculous price, and then hoping it grows into the valuation, is just asking for poor returns.

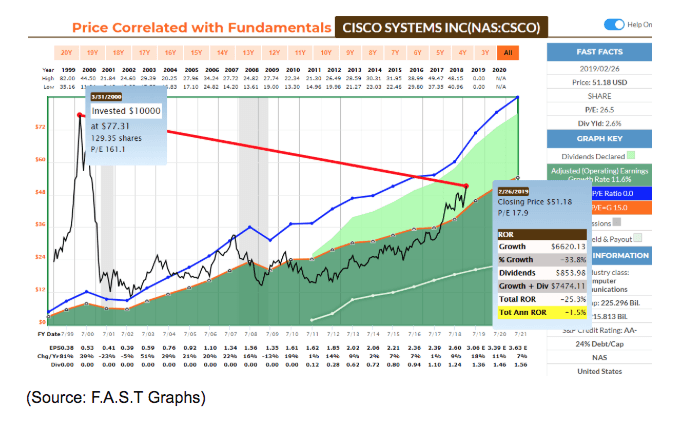

For example, at the height of the tech bubble, Cisco Systems (CSCO) was the most valuable company in the world because it literally made the backbone of the internet whose capacity was expected to double every year for the foreseeable future. But the tech bubble saw US market valuations soar to their highest levels in history, including Cisco trading at 161 times adjusted earnings in early 2000. Anyone who ignored valuations (and common sense) back then has seen a -1.5% annualized return over the past 20 years. That’s despite Cisco growing adjusted EPS by nearly 10 fold and paying a rapidly growing dividend since 2011.

The reason I’m bringing up the tech bubble isn’t just to make a very obvious point about not paying insane multiples for “hot” growth stocks. It’s also to point out that the same tech bubble that sent companies like Cisco into the stratosphere also made other investments dirt cheap.

Value stocks in particular (including Berkshire) crashed during the tech bubble (BRK fell 50% between 1997 and 2000) as the mania over growth stocks left even quality dividend stocks like Realty Income (O) trading at fire-sale prices.

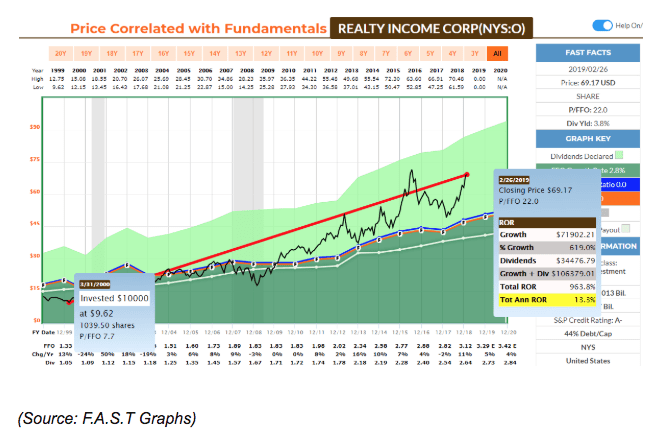

At the same time as Cisco was trading at 161 times earnings, Realty Income, a blue-chip REIT, was trading at 7.7 times FFO (REIT equivalent of a PE ratio) and a 10.2% yield. Had you bought Realty instead of Cisco at the time, then you’d have avoided Cisco’s 90% tech bubble crash and enjoyed a 127% rally in Realty (many value stocks went up during that epic bear market) between 2000 and 2002. And had you held onto your sky-high yielding shares, then you’d have also enjoyed a 13.3% CAGR total return today that multiplied your money nearly 11 fold over the past 19 years.

Of course, as Buffett just admitted, even masters of valuations can’t always get it right and there are dozens of ways to value a company. In my weekly “best dividend stocks to buy today” series, I explain three methods that I consider the most useful for regular investors and use for my own recommendations and portfolio buying decisions, as well as provide my five watchlists with plenty of great undervalued buy recommendations. Remember that no matter what the market is doing, something great is always on sale.

But there is another reason that overpaying for companies is a bad idea, and that’s because valuation is very closely tied with risk management. Buffett is famous for calling a company’s discount to intrinsic value its “margin of safety” and this brings us to the second crucial lesson we can learn from Buffett’s big Kraft mistake.

…Even the Best Blue-Chips Can Break

Kraft’s disaster came as a shock that included shares plunging 27% in a single day when the company revealed:

- A $15.4 billion write-down on core brands including Kraft and Oscar Meyers

- An SEC investigation into its accounting practices (which might require restating several years of earnings)

- A 36% dividend cut

- 2019 EBITDA guidance of a 10% decline (15% below analyst consensus)

This follows several years of mistakes. Years in which Kraft, which like many food companies, has struggled with changing consumer tastes and a shifting grocery retail environment, focused too much on cost cutting (due to 3G’s installed management) and not enough on adapting its brands to the new realities in which it operates.

Management cited “material cost savings that didn’t materialize” combined with falling prices (which it used to juice organic growth) as a reason for the EBITDA declines and margin erosion. Those necessitated cutting the dividend to free up $1 billion per year to more rapidly pay down its dangerously high leverage ratio (which had been rising steadily since 2012).

The point I’m making is that Kraft Heinz, which was a collection of some of the world’s most famous brands, lost its “wide moat” pricing power and several years of deteriorating fundamentals provided ample warning to investors that the dividend cut might be coming.

Now it’s certainly true that all blue-chips have to periodically adapt to changing conditions via restructuring. Even the famous dividend aristocrats and kings don’t achieve that status by experiencing 50+ years of perfect conditions and clockwork-like revenue and earnings growth.

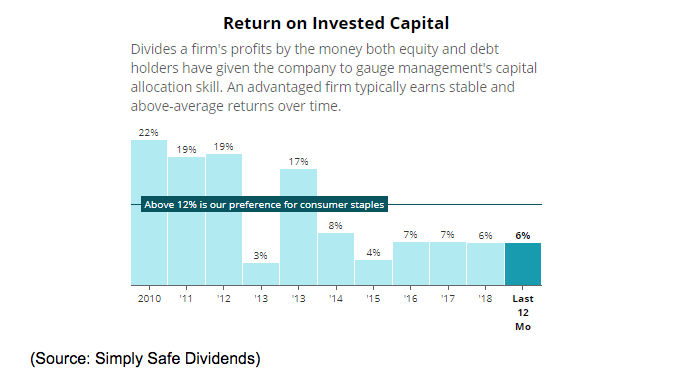

But when you see returns on invested capital (proxy for quality management) steadily falling over time like this, that’s a major warning sign that the thesis might be broken and it might be a good idea to sell before the wheels totally come off the bus (ie a dividend cut which usually causes shares to fall roughly as much).

But as Buffett himself has just shown us, even the greatest investor of all time can’t avoid owning a few stinkers in their portfolios. Which brings me to the final and most important lesson of all we can learn from Berkshire’s big mistake with Kraft Heinz.

Offense Wins Ballgames, Defense Wins Championships

Buffett is a fan of concentrated portfolios but even Berkshire’s $200 billion portfolio has over 60 holdings and his largest position makes up 20% of the portfolio. Most investors are better off owning 15 to 25 companies (plus any ETFs you may wish to use) and capping individual positions at 10% or less. Prior to Kraft’s epically terrible day, it represented about 7.5% of BRK’s portfolio.

Thus even though Kraft fell off a cliff, Berkshire’s portfolio only declined by a very manageable 2%. But good diversification is just one part of good risk management that has allowed Buffett to achieve his impressive returns despite the occasional big mistake like Kraft.

A bigger reason can be summed up by Buffett’s famous 2 rules of investing.

“Rule No. 1: Never lose money. Rule No. 2: Don’t forget rule No. 1”

Now it’s important to point out that Buffett is talking in broad strokes here, about avoiding large permanent losses of capital, ie realized losses. He doesn’t care about paper losses, and obviously avoiding all losses entirely is impossible if you invest long enough.

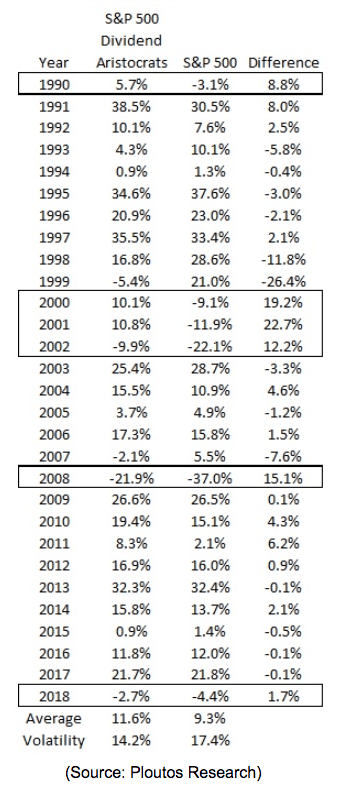

The general point Buffett and Munger (his right hand at Berkshire for decades) make is that great returns are not usually a result of epic wins, but rather avoiding costly losses. You can see what I mean by looking at the impressive return history of the famous dividend aristocrats (S&P 500 companies with 25+ consecutive years of dividend growth).

Over the past 28 years the aristocrats, the bluest of blue-chips and all mature and relatively slow growing companies, have managed to beat the market by 25% annually. They did this with 18% less volatility which is precisely why they managed to outperform over time.

You’ll notice that during bear markets (recessions) the aristocrats outperform the broader market, sometimes even rising (like double-digit gains in 2000 and 2001). During bull markets they seldom outperform and never by very much. Yet by merely falling less during down markets, and keeping up with bull markets, these boring dividend blue-chips have made investors rich and funded many a comfortable retirement.

This is the very approach my new Deep Value Dividend Growth Portfolio is using, with a pure focus on low-risk, undervalued dividend growth stocks (we’re beating the market by about 9% after 10 weeks).

Basically, never forget that Buffett didn’t become rich overnight, thanks to a few huge wins. He built Berkshire into a legendary company and made countless investors wealthy through a long-term focus on exponentially compounding market-beating returns over time, and always with a laser-like focus on risk management.

Bottom Line: Achieving Your Long-Term Investing Goals Requires Good Risk Management And Learning From Our (And Other People’s) Mistakes

Even the greatest investors in history are right 60% to 80% of the time. The reason they manage to get rich in the long-run is not because they never lose money, but due to their use of proper risk management — the cornerstone of their overall investing strategy.

This means buying quality stocks (at the time) at attractive valuations that create a margin of safety, in case the thesis breaks. It also requires diversifying enough so that a complete blowup of even the bluest of blue-chips doesn’t decimate your portfolio (GE was once a dividend aristocrat and the world’s most valuable company).

But most of all, it requires understanding that no one, not even the Oracle of Omaha, actually knows the future and that mistakes are inevitable. Stocks are called a “risk asset” for a reason because while they have potentially unlimited upside if things go right, they can also go to zero if the company’s fundamentals deteriorate badly enough.

Good long-term investing isn’t about hitting grand slams, like buying the next Amazon (AMZN), Apple (AAPL), or Netflix (NFLX). Successful investing is a game of probabilities using time tested strategies and sound risk management can help you hit enough singles and doubles to offset your strikeouts. Or to put another way, offense wins ballgames, defense wins championships.

While none of us can hope to recreate Buffett’s success in the future, by applying these principles we can maximize the chances of being exponentially richer over time, and eventually achieving our long-term financial goals.

About the Author: Adam Galas

Adam has spent years as a writer for The Motley Fool, Simply Safe Dividends, Seeking Alpha, and Dividend Sensei. His goal is to help people learn how to harness the power of dividend growth investing. Learn more about Adam’s background, along with links to his most recent articles. More...

9 "Must Own" Growth Stocks For 2019

Get Free Updates

Join thousands of investors who get the latest news, insights and top rated picks from StockNews.com!